Breadcrumb

Ventilator Liberation

Mechanical ventilation in the ICU setting is intended to be a supportive therapy: the ventilator can assist with the work of breathing until whatever issue required the ventilator in the first place has resolved sufficiently for the patient to be able to breath on their own. Ventilator liberation, the process of weaning the patient off the ventilator, is thus a crucial aspect of ventilator management.

A patient's readiness to be extubated should be assessed daily. This assessment includes several components. One aspect is to assess whether the patient's mentation has improved to the point where they can follow commands and thus protect their own airway. This can be assessed via a sedation vacation, where all sedative drips (fentanyl, propofol etc) are turned off to assess the patient's baseline mentation. A patient who does not become significantly agitated and is able to follow commands while off sedation has a greater chance of successful extubation. Daily sedation vacations are part of the "bundle" order set for mechanical ventilation at many institutions as they have been shown to decrease mortality and shorten hospital stays.

Aside from mental status the patient's clinical status must be assessed as well. Whatever issue required the patient to be intubated in the first place should be, if not resolved entirely, then at least significantly improved. Patients who present with pulmonary edema should be well diuresed. Patients who present in septic shock should have received appropriate anti-microbial therapy. While patients on vasopressors (such as Levophed) can be extubated, it is preferable that they have been weaned to a relatively low dose (patients who are "maxed" on multiple pressors are not likely to tolerate extubation well). Any electrolyte abnormalities should be corrected.

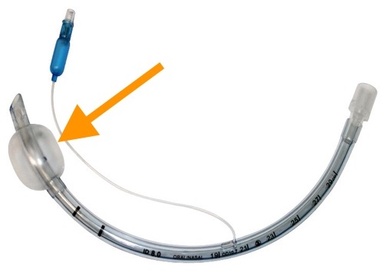

There are other issues that should be addressed as well. One is the presence (or absence) of a "cuff leak." Endotracheal tubes come with an inflatable cuff (highlighted by the orange arrow on the picture to the left) that is inflated when the tube is inserted. Prior to extubation the cuff is often deflated to assess for air flow around the cuff; if a "cuff leak" is present, this is considered a good sign that the patient is ready for extubation. Absence of a cuff leak can indicate the presence of laryngeal edema (due to, for example, a traumatic intubation or a prolonged period of intubation), which may make the patient less likely to tolerate extubation.

An intact, strong cough is another quality that predicts a successful extubation. Patients who are able to produce a strong cough to clear their own secretions are more likely to tolerate extubation.

Finally all the pieces can be put together in a spontaneous breathing trial (SBT). Here sedation will be turned off and the patient will be put on a spontaneous ventilation mode, such as Pressure Support, where they will need to initiate and do the bulk of the work for every breath they take. The ventilator will only provide minimal assistance (e.g., a PEEP of 5 cm H20 and a pressure support of 5 cm H2O). While there are no universally agreed-upon criteria for what constitutes a successful SBT, tachycardia, tachypnea, hypoxia or subjective agitation or distress are all signs that the patient may not tolerate extubation.

One index that is sometimes used is the rapid shallow breathing index (RSBI). The RSBI is equal to the respiratory rate divided by the tidal volume (RSBI = RR/TV). A high respiratory rate (tachypnea), accompanied by a low tidal volume (indicating poor underlying respiratory mechanics) is a poor prognostic factor for successful extubation. An RSBI greater than 105 min/L is often cited as indicating a lower chance of a patient tolerating extubation.